How to Play

When I introduce this problem to students, I don’t initially display the poster. Instead, I recreate the poster on a whiteboard using a 4 digit number supplied by one of my students.

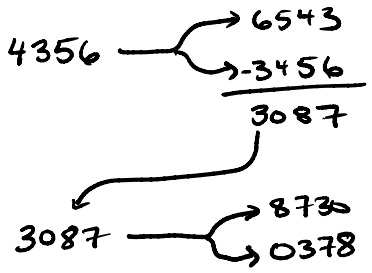

Before I finish my second iteration, I pause and ask them to pick their own number and try it on their own. I tell them to keep going until something interesting happens.

Tasting Notes

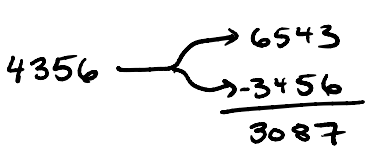

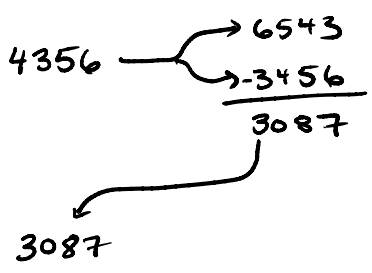

Clarify the leading zero: The example on the poster intentionally includes 0 as one of the digits so that we can model how to use a leading zero to keep the numbers four digits long.

Find the fixed point: Every student eventually ends up at 6174, and it is really fun to see them notice that they are stuck in a loop. For some students, this happens quickly. For some students, it takes a while, and I might have to reassure them that something interesting will happen eventually. Some students get in such a flow that they don’t notice that they’ve done the same thing multiple times until I ask them to step back and notice things.

What did other people get? When groups get stuck at 6174, I ask them to compare their results to someone else (this is especially nice if we’re on vertical whiteboards). Students notice that other groups ended up at the same number, which is often surprising. They might note that other groups got there faster or slower, which they might find worth investigating further. They might wonder if you will always end up at 6174.

Try another starting number: I often ask students to try it again with another number. Before they start, I ask what they think will happen. I encourage them to keep trying new numbers until they seem fairly certain they will end up at 6174.

Find the exception to the rule: Not every number ends up at 6174! There is an exception, and students often feel clever for finding it. Starting with something like 3333, we get stuck at 0000 right away.

Where It Comes From

I’m not sure where I first saw this problem, but I’ve seen several versions and references to it. Usually, it is called something like “Kaprekar’s Routine” or “Kaprekar’s Constant.” D. R. Kaprekar was an Indian recreational mathematician who discovered this process/constant. I don’t usually love when mathematical objects are named after people, but it is nice that for once it isn’t a white man.

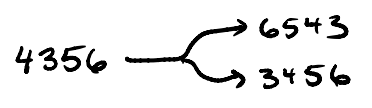

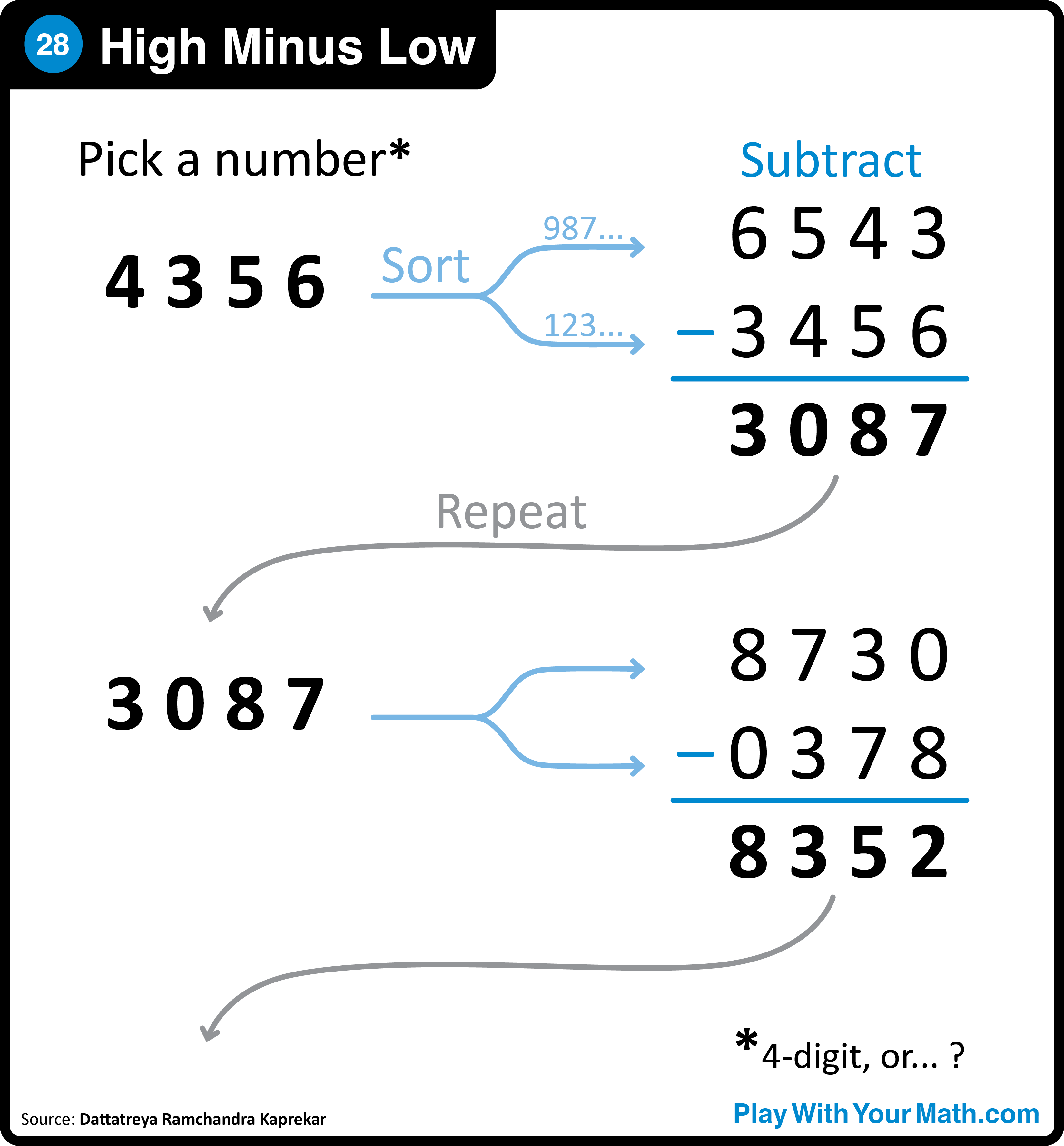

This problem has been on our ideas list for probably a decade, and it is probably one of my most used Play problems with students. But the design took a long time. I always knew we wanted to show an example or two, but it was hard to organize the flow. I used to write the sorted numbers below the original but then it looked like it was part of the subtraction, which is also vertical. Sorting horizontally made both the design and the problem more intuitive.

Why It Matters

Fewest words yet: We strive for a succinct and visual statement of the problem, and this poster uses only 6 words! In fact, there isn’t even a question! But we still hope the arrows and example make the process clear and evoke curiosity.

A playful warm up: Students can appreciate this problem after only playing for 5-10 minutes, so it makes a great warm up at the start of class.

Introduce iteration: This problem shows how an iterative function can converge, and I like to use it when teaching more complicated iterative processes, such as Newton’s method in a Calculus class or the Mandelbrot set when teaching complex numbers.

Practice problem posing: I like to ask students, what should we try next? Usually, we start by trying another four digit number, but that gets boring eventually. So what next? I could just tell them, but this problem is a good moment to ask students to think about what they could change in the problem in order to keep playing. For example, we could add instead of subtracting. Or we can start with a different number of digits.

Variations

Different number of digits: It’s worth exploring what happens to 3-digit, 2-digit, and 5-digit numbers to see how the results are similar and different to the 4-digit case.

Automate the process: For computer science students, writing a program that automates the process of sorting and subtracting is a fun challenge. I used CS Academy to make my own interactive 3-digit version of the problem to use with my students. In my version, if you click on the top number, you can select your own starting number. If you press the space bar, it will iterate. I’ve found that this process gets tedious for more than 4 digits, so automation becomes really useful for further exploration.

Prove it: Students quickly suspect that (almost) every starting number will end up at 6174. How many starting numbers are there? Can you show that they all eventually get there? The proof would likely require organizing the four digit numbers into a sort of flow chart or web.